“The science we need for the ocean we want” is the slogan of the Decade of Ocean Sciences for Sustainable Development (2021-2030), spearheaded by UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC). This formula, echoed in the title of the report published by the IOC in 2020 [1], sums up the vision and roadmap. Proclaimed by the United Nations on December 5, 2017 and entrusted to UNESCO, this decade aims to mobilize the international community around issues related to ocean knowledge, management and protection. With 150 member states, the IOC’s main mission is to strengthen international scientific cooperation and promote innovative technologies linking ocean science to the needs of society. IOC’s ambition is twofold: to provide sound scientific knowledge for international political action, while encouraging the development of open, collaborative ocean research focused on contemporary challenges.

After a first United Nations Ocean Conference (UNOC) in New York in 2017 and then a second in Lisbon in 2021, both of which ended in state pledges without binding agreements, France and Costa Rica have decided to co-organize a third UNOC from June 9 to 13, 2025, in Nice. The organizers of this new edition have emphasized the desire to integrate scientific knowledge more directly, translated into recommendations to feed into political discussions. For the first time, just prior to the UNOC, a scientific congress was organized, the One Ocean Science Congress (OOSC). This congress was also held in Nice, from June 3 to 6, 2025, in the very premises that are destined to host the diplomatic conference, and resulted in a manifesto [2]. Written by the organizers and members of the conference’s scientific commission, the manifesto includes scientific recommendations for the political leaders attending the UNOC. All OOSC scientists were asked to sign the manifesto.

As a student of environmental science and policy, with a focus on international relations, I’m particularly interested in platforms at the interface between science and politics. I observe and try to understand the role that science plays in political discussions on climate: how certain scientific studies are selected, interpreted and mobilized by public decision-makers, and in turn, what decisions influence research priorities. In this context, I studied the integration of biogeochemistry into the negotiations of the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) [3]. I conducted a comparative semantic analysis of scientific documents, institutional discourses and treaty texts, in order to shed light on the place this discipline takes (or not) in governance dynamics. Having also worked briefly in the UN system — at the French Association for the United Nations (AFNU) and with UNESCO’s scientific unit — I am interested in the mechanisms by which international organizations set certain global scientific objectives, while drawing on research findings to build their action programs.

Given that few, if any, biogeochemical studies were presented at the OOSC, I approached this week of observation without a clear approach. I attended various conferences on a variety of topics (mCDR, ocean-based solutions, technologies, marine connectivity, indigenous knowledge, research funding, governance and management, capacity building, science-policy links, international legal agreements). My observation focused on the speakers’ speeches and presentations. I hoped to observe the construction of a new scientific diplomacy. What is this science that “we” “need”, and how is it being promoted? How do scientists express their ideas to influence politicians? During the conferences, I took notes of the speakers’ speeches, trying to faithfully retrace their expressions. Without going into the technicalities of the lectures, which differed from subject to subject and discipline to discipline, I began to identify common themes, notably data sharing and the importance of collaboration.

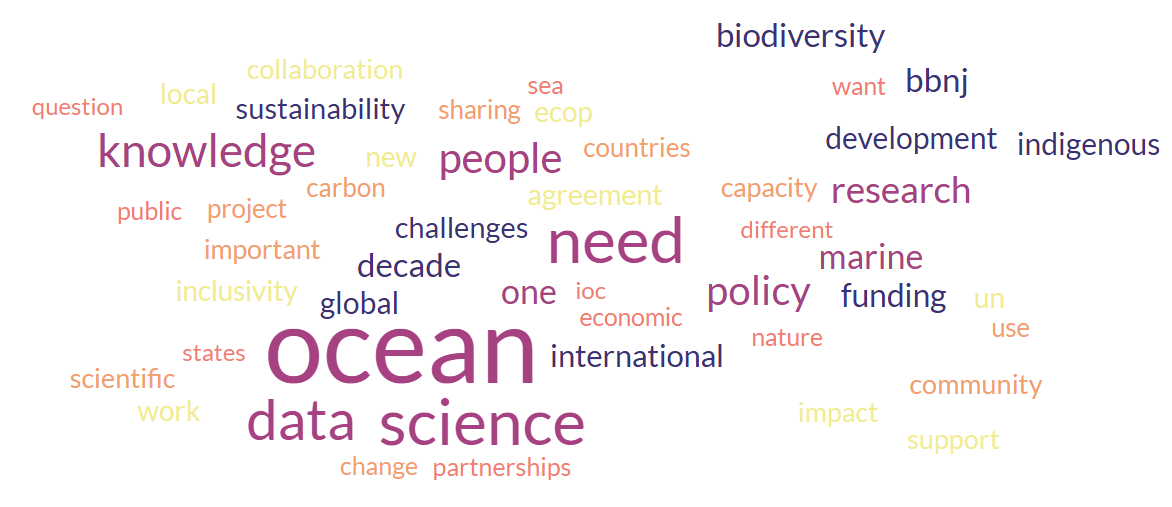

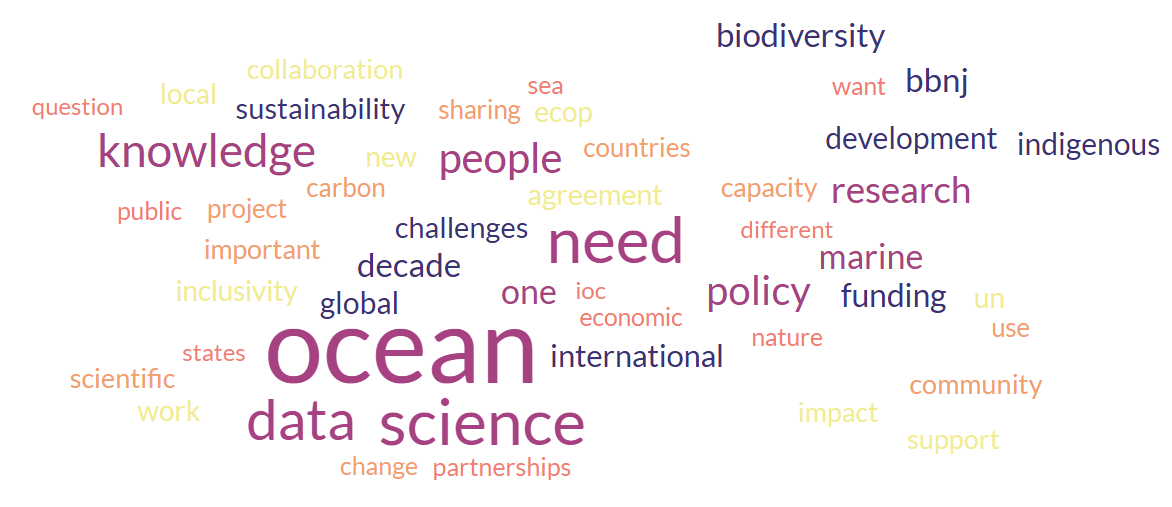

By inserting my notes, a corpus of over 15,200 words, into the Free World Cloud Generator online software, I generated a cloud of 50 words (Figure 2). Because of the textual corpus on which I relied, this word cloud is in fact based on my understanding of the discourses – rather than reflecting their exact content. It is therefore de facto situated, but provides a first glimpse of how these discourses may be received.

Unsurprisingly, the most frequently used terms are “ocean” and “science”, confirming the congress’ main theme of ocean sciences. Several common themes emerged, which were often not the focus of the speakers’ presentations, but emerged as topics and avenues for improving scientific research, in order to better inform public policy.

First of all, we note the recurrence of the term “data”, which reflects speeches supporting the importance of data and the need to collect more data. In particular, this would require more infrastructure and financial resources. The discourses also militate in favor of free access to data. We also note the term “knowledge”, which refers to both acquired and traditional knowledge, particularly that of local and indigenous populations. We can see here a desire to consider and reconcile all types of knowledge, whether they emanate from old or new scientific discoveries, or whether they are traditional. This emphasis may be an indication of the porosity between UN multilateralism and the scientific conference, insofar as the emphasis on local and indigenous knowledge is usually far less systematic among the research communities most represented at the congress.

The recurrent invocation of “collaboration” is another salient feature of this “on-the-spot” extraction, as evidenced by the recurrent use of terms belonging to its lexical field, such as “partnerships”, “agreement” or “sharing”. The need for collaboration, supported by the speakers, is also described as an objective of the congress, with the desire to create “one”, a unity, an ocean. This raises the question of how scientists use the terms associated with collaboration. Are scientists appropriating the vocabulary and political ideas of the organizers of the Decade of Ocean Sciences, hoping to make their work easier to appreciate? Or have the decade’s objectives emerged in response to requests from the scientific community? It could also be a mixture of both.

While many speakers seem to advocate collaboration, the term is rather vague and, taken out of context, meaningless. This need for collaboration is most often backed up by the qualifier “international”. Some speakers suggest “capacity (building)” exercises, i.e. collaboration through the construction of collective skills. However, these evocations tell us little about the meaning lent to the vocabulary of collaboration: the notion of collaboration undoubtedly does not refer to the same practices depending on the disciplines or stakeholders involved. For a marine biologist, it might mean sharing biodiversity data; for a physicist, co-modeling ocean currents; for a sociologist, dialogue with local communities. On the political side, an international representative might see it as a negotiation process, while an NGO member might see it more as a form of collective mobilization in favor of the oceans. Should the science we need be based on the sharing of ideas and data within a single discipline, or on a cross-disciplinary approach to knowledge, or on collaboration that transcends geographical boundaries? To date, we have little evidence to shed light on the notion of collaboration – other than to assume that its widespread use confers on it the value of a public virtue for the scientific community, one that deserves to be emphasized in this particular time and place.

During the same OOSC session, it happened that two speakers defended very different visions of scientific collaboration. For example, during Wednesday morning’s Keynote Session — the first of the conference — Michelle Bender, a lawyer specializing in the law of nature, argued for a collective paradigm shift in our relationship with the ocean. She called for us to move beyond an anthropocentric approach by recognizing the oceans as legal entities in their own right, and developing a science not based on what “we” need, but on what the oceans need to preserve their ecosystems. On the other hand, Takashi Gojobori, from the MaOI (Marine Open Innovation) Institute, a biogeochemist and expert in numerical modeling, advocated an approach centered on the accumulation of data via massive scientific collaborations, with a strong investment in artificial intelligence. The coexistence of these two visions at the conference raises an important question: can we truly respect the oceans as an end in itself, if the tools we use to understand them are based on models built by and for humans? This question was raised by a member of the audience. The speakers asserted that they did not see any incompatibility between the two approaches, without however proposing any solid arguments to support the possibility of such conciliation.

Admittedly, the notion of collaboration remains vague, but the OOSC format seems to have been designed to encourage its emergence. Unlike a traditional scientific conference, OOSC featured sessions organized by theme rather than by discipline. This approach was clearly intended to encourage a holistic study of the subject, crossing angles of analysis and speaker profiles, encouraging each speaker to take an interest in – or at least confront – areas outside their expertise. The underlying gamble is that, by stimulating scientists’ intellectual curiosity, this method will lead to the emergence of new questions and encourage interdisciplinary dynamics. In the same way that oceanography and meteorology came together in the mid-19th century to give rise to the climate sciences, the aim is to pave the way for a unified science of the ocean, reconciling – or at least bringing together – knowledge from different disciplines that have the ocean as their object of study. As the OOSC unfolds, it becomes clear that the organizers see such a holistic vision as likely both to provide a better understanding of marine issues and to guide the actions to be taken.

But for this ambition to become a reality, scientific collaboration is not enough: political cooperation is just as essential. And the link between the quality of the former and that of the latter is not so clear…

– – –

References

[1] The United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development, (2020), The science we need for the ocean we want, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000265198/PDF/265198eng.pdf.multi

[2] IFREMER, OOSC, CNRS., One Ocean Science Congress Manifesto, (05.06.2025), https://forms.ifremer.fr/pdg/oosc-manifesto/

[3] Astruc Delor, C., Delavande, C., and Durfort, A.: Governing a resilient ocean under uncertainty: Lessons from a Semantic Analysis of Knowledge Integration and Environmental Decision-Making in the Southern Ocean, One Ocean Science Congress 2025, Nice, France, 3–6 Jun 2025, OOS2025-1180, https://doi.org/10.5194/oos2025-1180, 2025., https://meetingorganizer.copernicus.org/OOS2025/OOS2025-1180.html

Share