Monday, 2 June 2025. It is 8:30 a.m. when our ODIPE collective passes through the security gates installed at the Port Lympia site in Nice for the One Ocean Scientific Congress, held ahead of the United Nations Ocean Conference. The scale of the security measures seems disproportionate to the small number of visitors making their way to the main hall – purpose-built for the occasion and soberly named “Room 1” – to attend the congress’s opening [1] session. Yet, according to the promotional video, the congress brings together more than 2,000 participants from around the world. The room follows standard UN conventions: each seat is equipped with a microphone and headset, allowing the audience to listen to live translation of the speakers’ remarks and/or ask questions.

Figure 1. View of “Room 1” during the opening ceremony (02/06/2025, credits: Juliette Kon Kam King).

There will, however, be no questions this morning. The session is devoted to a succession of speeches by the congress organisers, scientists, and politicians – most of whom are men.

The purpose of the event is to bring together a scientific community “united around a common emergency”: the protection of the planet’s largest yet most vulnerable “resource”, the ocean. The desire to highlight science and (re)affirm its role lies at the heart of the speeches by Christian Estrosi, Mayor of Nice; François Houllier and Antoine Petit, Presidents of IFREMER and CNRS respectively; and Peter Thompson, Special Envoy of the United Nations Secretary-General for the Ocean.

While the introductory video reminds us that the scientific community exists to “provide robust, actionable, and essential scientific knowledge” to inform public policy, the former Director of CNES (the National Centre for Space Studies) stresses that the conference is not merely about bringing experts together, but about uniting them and forming a “crew sailing towards the same goal”: understanding and protecting the ocean.

The challenge facing the conference is clear: protecting the ocean, of course, but also gathering a community of scientific experts who may appear scattered or fragmented, given the many themes, disciplines, and institutions involved. Affirming the importance of the ocean, certainly, but also that of “science”. “There is only scientific truth, and it is good to remember this in these times of doubt and anti-scientific temptations,” asserts Christian Estrosi, while the French Minister of Higher Education and Research evokes the geopolitical tensions weakening networks and funding for international scientific initiatives.

As the sessions following the opening ceremony unfold, the importance of protecting science itself becomes increasingly evident. Far from being an exclusively “academic” scientific conference, the week’s presentations actively contribute to networking among scientific actors – and with other stakeholders, particularly from the private sector – while addressing the political and societal role of science and the financial resources required for its development. The congress thus takes part in the demarcation and legitimisation of an ocean science community which, according to Jean-Pierre Gattuso, oceanographer at CNRS and co-chair of the congress, aims to serve as the “scientific pillar” of the upcoming United Nations Conference.

These dynamics become particularly clear when it comes to the deep sea. This year, the deep sea takes centre stage, illustrated by a dedicated theme: “Knowledge of the deep sea and means to enable its sustainable exploitation”. This topic will be discussed throughout the week and followed closely by part of our research team.

The prominence given to the deep sea is even more striking when contrasted with the previous United Nations Ocean Conference, held in Lisbon in 2022. That conference was not preceded by a scientific event but by one aimed at young people. Moreover, the deep sea did not appear on the conference’s official agenda. It featured only in two types of parallel events: those organised by non-governmental organisations to raise awareness of deep-sea protection issues (Figure 1), and those organised by the Secretariat of the International Seabed Authority (ISA), which highlighted the agency’s work in regulating mining beyond national jurisdictions. These events showcased its stated commitment to “good governance”, frequently associated with “sustainable development” and cooperation with “science”. Through these two groups of actors, the scientific community’s views on the deep seabed were indirectly conveyed.

Figure 2. Scientists Diva Amon and Sylvia Earle (left) at the NGO Ocean Basecamp during UNOC2 in Lisbon (30 June 2022 – credit: Tiago Pires da Cruz).

Three years later, the scientific and political focus on the deep sea raises questions about the role of the One Ocean Science Congress in assembling and legitimising “a” scientific community around these issues. Theme 4 of the congress provides these communities with shared visibility. The sessions attract an audience and speakers who are often the same from one presentation to the next: within the congress, the community appears relatively stable and well defined. These actors know one another and have prepared for these events in advance.

Although this issue mobilises an already well-established scientific community, it does not appear unified. It brings together a range of institutional actors and individuals who play diverse roles in producing and disseminating knowledge. Participants come from several disciplines, primarily environmental sciences and Earth system sciences. There are also lawyers and, more rarely, representatives of the humanities and social sciences. Yet the participants are not solely researchers. Many are affiliated with various organisations. A number of them straddle several worlds: academic research, consultancy, private companies, and large non-governmental organisations. This diversity is reflected in the presentations: some researchers participate in a personal capacity to showcase findings or publications, while others speak on behalf of their institution or network. Certain individuals therefore appear under different affiliations depending on the session. The conference also offers an opportunity to observe the emergence of new actors and the difficulties of funding deep-sea science, which is particularly costly. For instance, companies specialising in scientific deep-sea exploration have a dedicated space in the congress’s secondary area – where numerous parallel events take place – and feature on certain panels.

Throughout the sessions, diverse collaborative networks emerge – sometimes overlapping, sometimes distinct. A recurring aspiration is to bring these various actors and networks together. The CNRS “Deep Sea” Working Group gives the floor to the European Marine Board to present its new report; the Deep Ocean Stewardship Initiative and the Deep Ocean Observing Strategy appear on the same panels; the team promoting the creation of IPOS (International Platform for Ocean Sustainability) identifies and invites these actors to its events.

Figure 3. Presentation on seamounts by Lissette Victorero (DOSI) at an event on the seabed (04/06/2025 – credits: Tiago Pires da Cruz).

In most cases, scientific research is deeply intertwined with political and strategic dynamics. The conference therefore serves both as a platform for presenting scientific projects and a forum for strategic mobilisation. For several speakers, the event is an opportunity to explicitly defend funding for scientific research and to articulate a political stance on current perspectives regarding seabed use. Mining extraction is at the centre of most of these debates.

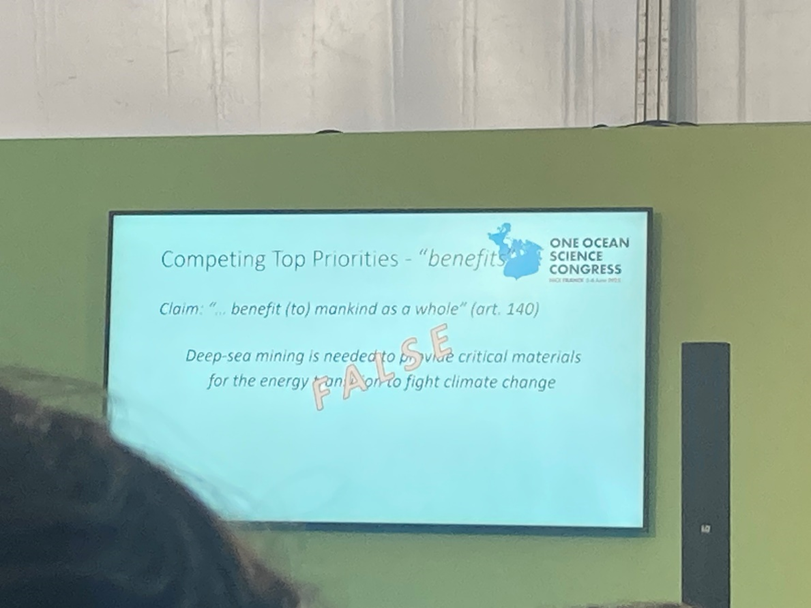

Indeed, few presentations over the week fail to address these concerns. The omnipresence of mining issues reflects the hybrid nature of the event, which is presented as a scientific congress but is explicitly linked to the UN framework that follows. A common narrative emerges across most presentations. On the one hand, speakers repeatedly emphasise that the seabed remains (far) too little known and that scientific knowledge must be expanded. On the other hand, they stress that existing knowledge is already sufficient to demonstrate the lasting environmental damage caused by mining and to argue for applying the precautionary principle in the face of extractive ambitions. During one presentation, a panellist promptly refuted the supposed benefits of mining (see Figure 3), while two researchers – both also involved in conservation NGOs – presented a scientific publication advocating a moratorium on such extractive developments.

Figure 4. Presentation on seabed mining (03/06/2025 – credits: Juliette Kon Kam King).

The congress underscores the influence of the international political agenda on the scientific community working on the seabed. Although diverse and eclectic, this community appears driven by a desire to position itself as a key player in seabed governance and in debates surrounding mining. This discourse, developed in international arenas since the 2021 IUCN World Conservation Congress in Marseille, is defended with renewed vigour here. It is reflected both in an online statement signed by nearly one thousand scientists and in the congress’s final declaration [2]. In a context marked by the beginning of President Donald Trump’s second term, the seabed scientific community gathered in Nice explicitly highlights the threats it perceives: mining and public disinvestment in ocean science. Conservation and scientific research thus emerge as the participants’ priority objectives, encapsulated in what appears to be the congress’s guiding slogan: “you can’t protect what you don’t know.”

[1] This session is publicly available here: https://www.youtube.com/live/XOSGl7PIXvM (accessed on 06/09/25).

[2] https://seabedminingsciencestatement.org/

Share