The term “One Ocean” today aims to be inclusive, aligned with the principle of “leaving no one behind,” which is central to the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science.[1] Yet institutional practices still struggle to reflect this commitment. At the opening of the One Ocean Science Congress (OOSC) on June 3, the inaugural session included thirteen men and only one woman — a revealing imbalance that exposes persistent gender biases in visible speaking roles (Johanessen, 2024, p. 69).[2] While better representation was observed in subsequent panels, the situation remains uneven: at the Blue Economy Forum in Monaco, the issue of equity seemed completely absent. Cristina Tebar Less (Women for Sea, WfS) notably highlighted this during the presentation of Women Action for the Ocean (WAO) in an amphitheater at the Mediterranean University Center (CUM), where access was strictly by invitation only.

Analyzing how equity is manifested in marine sciences presented at the OOSC reveals a persistent marginalization of social sciences, often confined to themes related to researchers from the Global South or indigenous communities. This dynamic reflects a deeper imbalance: the inclusive and legitimate participation of holders of Indigenous cultural knowledge remains largely marginal, as indicated by the implementation plan of the United Nations Decade (Hills et al., 2022, p. 281).[3] This is despite the fact that local and Indigenous knowledge (Indigenous Local Knowledge – ILK) is officially recognized as essential in the guiding documents of the same Decade (UNESCO, 2021).

Although Indigenous peoples represent only about 5% of the global population, they protect nearly 85% of the world’s biodiversity (Nelson, June 2, 2024).[4] This paradox highlights the crucial role of their knowledge in ecosystem management — knowledge that has historically been marginalized (Vierros et al., 2008).[5] Indeed, Western knowledge has often imposed itself as universal, based on rigid dichotomies (subject/object, reason/emotion, mind/body, nature/culture, man/woman, white/black), relegating other forms of knowledge to the status of irrational practices and consequently destroying them (Santos, 2014).[6] The attempt to dissociate Indigenous local knowledge from the ways of life that produce it reveals an extractivist logic inspired by colonialism and capitalism, which transforms this knowledge into resources to be exploited. As Todd (2015, p. 17) emphasizes, such an approach amounts to “erasing the embodied, practical, and legal dimensions of Indigenous ontologies as they are enacted by local actors.”[7]

So where were forms of equity and the presence of plural knowledge observed during the OOSC? In the panel T1-1a Plurality of value and knowledge systems, including Indigenous and local (within Theme 1: Integrating knowledge systems, with a focus on responsibility and respect for the ocean), a member of a local community, Rahera Ohia, who spoke alongside postdoctoral researcher François Thoral, both from the University of Waikato, New Zealand, took the floor: “Scientists, you need us. You will come to us, because without us, you will not find what you are looking for.” This statement resonates deeply with Indigenous communities worldwide, as shown for example by Ailton Krenak in his book The Future is Ancestral.[8]

In the same panel (T1-1b), Karen Fisher, an environmental geographer from the University of Auckland, cautioned that while we support the inclusion of Indigenous peoples and their knowledge in efforts to improve human-ocean relationships, we must insist on respecting the integrity of these peoples and their knowledge. Speaking from Aotearoa (New Zealand), she recalled the ongoing struggles for their rights, as well as the epistemic violences and injustices stemming from colonization. Her intervention raised a central question: in this United Nations Decade of Ocean Science, who does the “we” refer to in the slogan “the ocean we want”?

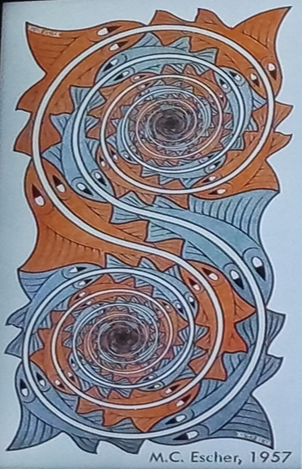

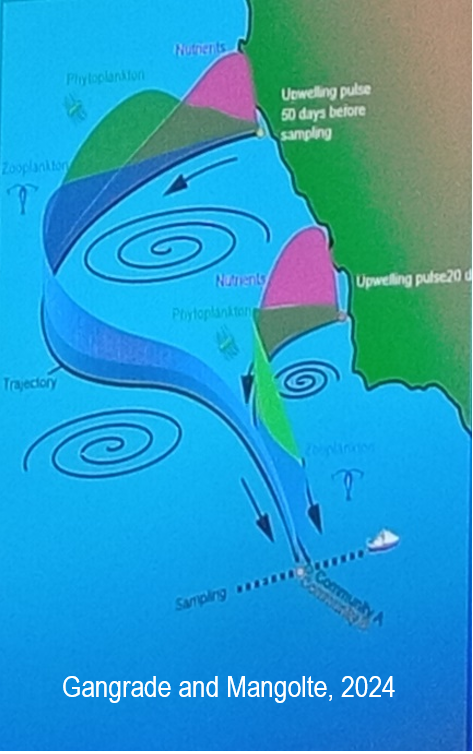

Meanwhile, Marina Lévy, an oceanographer specializing in modeling and advisor on Ocean matters and IRD president, highlighted the limitations of ocean exploration—whether based on observation or modeling—due to our inability to observe the ocean in a synoptic manner, over time, and at all scales. She stressed the importance of reconciling different physical spatiotemporal scales to assess ocean health, emphasizing primary production as a key indicator. This is observed via satellite and integrates physical, chemical, and biological dynamics. She also mentioned the value of integrating Indigenous knowledge and decision-making processes into these assessments. As she noted during her presentation, after several years of research, she found a resonance between her scientific data and a creative work that, in her view, visually expresses what her data reveals about the ocean.

|

These two illustrations were part of Marina Lévy’s presentation during panel T1-1a; the second diagram comes from collaborative work conducted in Peru with Alice Pietri, IRD.

How then, can we integrate two such different epistemological frameworks? How can we build a holistic approach to research?

|

|

Several presentations addressed this question, notably that of Pieter Romer, liaison officer with Indigenous communities at Ocean Networks Canada (ONC), who spoke in panel T1-1b. He emphasized the need to empower local actors within their own environments by providing them with training and tools. In his presentation titled “The advancement of Indigenous involvement in ocean monitoring through meaningful engagement and true partnerships,” he highlighted how crucial Indigenous communities’ participation in data collection is for long-term monitoring and achieving more robust results. He also pointed out that Indigenous monitoring methods, often qualitative and low-cost, bring voices and perspectives that conventional science cannot afford to ignore. ONC, an initiative of the University of Victoria, manages marine monitoring programs in coastal, deep ocean, and Arctic environments. By combining Indigenous and local knowledge—including Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), Local Ecological Knowledge (LEK), and Indigenous Knowledge (IK)—environmental governance and resource management decisions can be improved.

Mia Strand, a social science researcher at Nelson Mandela University (South Africa), also present in panel T1-1b, questioned how to ensure that this transdisciplinarity does not harm non-academic collaborators such as Indigenous knowledge holders or fishing communities. Might it not become another form of extractive research? At its core, this raises a question of understanding at a different scale.

What initially seemed impossible—interdisciplinarity or transdisciplinarity—becomes an asset when genuine collaborative work begins to take shape. This research model has its appeal but must be mobilized or invoked with vigilance and a keen awareness of the difficulty of resisting its entanglement in cognitive and political infrastructures whose extractive logic is only rarely absent. Only then can we speak of one ocean, in the singular.

There are examples of close and spiritual relationships between humans, deities, and marine cultures involving migratory species such as whales, dolphins, sharks, and turtles that travel vast areas of the Pacific (Lebic, 1989; Luomala, 1984; Oliver, 1974).[9] However, by labeling non-European traditions and practices as “culture,” “tradition,” or “belief”—in other words, as forms of “non-knowledge”—these knowledge systems are relegated and prevented from coexisting with Western knowledge (Santos, 2014).[10] Since we are already immersed in the practices and worldviews of local communities, whose ways of relating to the ocean stem from a completely different ontology, Catherine Sabinot, an anthropologist at IRD Noumea and participant in the second session of panel T1-1b, asked: can Oceanian ways of relating to the ocean transform our management methods and human-nature relationships?

To raise awareness of the importance of genuine inclusion for understanding the environment, the ocean, and its living beings, one evening we climbed to Fort Mont Alban to attend the Sentiment Océanique workshops, to listen to the sound recordings shared by Olivier Adam, a bioacoustics researcher at the Institut d’Alembert, through performing arts. As he says: “Marine creatures speak to us… but who listens?” Scientific advances focusing on their consciousness and social lives show these animals are far more complex than once believed, as mentioned by Hortense Chauvin in an article published on Reporterre on May 7, 2025.[11] Lynne Sneddon, professor at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, and a renowned fish specialist, adds: “Fish do not have facial expressions, which humans rely on heavily to understand others,” but “does that mean they are amnesiac and devoid of sensitivity?”[12]

Indeed, when science is shared, and when we step out of highly secured spaces like Port Lympia these days in Nice, we can have the pleasure of touching the real world, the natural world, by watching and listening, for example, to the dance of the Minuit 12 collective with the work Récifs at Fort Mont Alban. There, on a Friday evening, with one of the best views of Nice, the living bodies of the dancers express themselves to the rhythm of voices demanding to be heard—voices of cetaceans recorded by Olivier Adam and the sound creation of Inès Ramdane. The bodies act, moved by the effervescence of voices of lives disrupted in the marine environment. These recordings by Olivier Adam have also been part of other transdisciplinary works, including a collaboration with Nicolas Dubreuil, who has lived for a long time in Kullorsuaq (Greenland). Together, they presented this project at Océanopolis (Brest).[13] Through the recorded sounds of narwhals, Olivier Adam helped Nicolas realise that the Indigenous community constantly listens to them, often without even consciously noticing, because they have long lived in symbiosis with these animals. These communities listen to sound communication with narwhals through the paddle blades as they move in their canoes. Narwhals are thus an integral part of the cosmogony and daily life of this Arctic Indigenous community.

At the immersive space La Baleine on the morning of Saturday, June 7, collectives and local and Indigenous communities from all over the world were bustling. They had been chosen to represent precisely their communities, their often invisibilized voices. They were preparing for the major UN Ocean Conference (UNOC) event in the presence of heads of state. Gathered in a circle with an event coordinator guiding them on how to intervene, they were getting ready for the closed-door meeting on Sunday, which would be broadcast through communication channels and would mark their presence together with political decision-makers.

But on Saturday, in the closed rooms located on the upper floor of La Baleine, they also participated in various events organised by NGOs and collectives. For example, during a presentation dedicated to the knowledge of the Kanak people, one could hear the ocean vision expressed by Maina Sage, former deputy for French Polynesia to the National Assembly from 2014 to 2022, present in the audience. When addressed by one of the speakers, Tamatoa Bambridge, she responded:

“A bit of a surprise question, but thank you. So, this Polynesian vision of the seabed is very important today. Because with deep-sea mining, we are very worried; it’s a real concern. Because Polynesians see the seabed as a sacred space. It is sacred at all times. Because it is the source, truly the matrix of our origins. And also, as my colleague from New Caledonia said, it is also where the souls of our ancestors go. So this space is sacred; we call it the ‘Papa,’[14] and if we return to this concept of genealogy, for us, our genealogy starts at the ‘Papa.’ That is to say, we associate our genealogy with the ‘Papa,’ the foundation, meaning where we are from, our island. And we see, as in New Caledonia, all the species around us as members of our family.

So, when we talk about genealogy, we talk about the ‘Papa,’ and then we ask, we say ‘fata Papa’ in Paumotu, and we recite its genealogy likewise the construction of the reef, with the building of its different layers up to today. So if we want to talk about a family tree, we can even go further and, instead of talking about a tree, talk about a reef. Our family tree is the construction of a reef. So, we do not see the world the same way as Westerners; we see the world as a space where everything is connected. And if we saw the world that way, perhaps we wouldn’t have so many problems today. Everything is linked to a soul: a fish, a whale, and a shark have equal importance, and we cannot dominate this world. We are the ocean. And the ocean is an entity, a living entity. That is what I can share today.”

Contrary to a Western vision that is often utilitarian, this Polynesian approach translates into support from jurists seeking legal recognition of the ocean as a living organism.[15] As scientists Gattuso et al. (2021)[16] mention, the study by Breitburg et al. (2018)[17] revealed that oxygen minimum zones in the open ocean have expanded over several million square kilometers, and hundreds of coastal sites now exhibit oxygen concentrations low enough to limit animal populations and disrupt the cycles of essential nutrients. The volume of oxygen-poor zones is expected to increase by about 7% by 2100 under a high CO₂ emissions scenario. Deoxygenation affects biodiversity and food chains, negatively impacting food security and the livelihoods of dependent populations.

Christina Hicks, an environmental social science researcher within the political ecology group at the Centre for Environment at Lancaster University, during keynote 5 titled “Diverse Food Systems Support Justice and Nutrition,” who emphasized the crucial importance of small-scale fisheries for food security and nutrition of local populations, notably in Africa and Asia. She stressed the nutritional richness of fish, beyond proteins, highlighting essential micronutrients for physical and mental development. Despite sufficient availability of nutritious fish in some regions, inequalities in access persist, often linked to industrial fishing practices, global trade, and governance.

Christina Hicks also highlighted climate threats and the need for equitable and inclusive marine resource management to protect these diverse and essential food systems. Thus, even though oxygen supply for humans is not a source of concern, it is important to address the increasing movement of fish to other areas due to the expansion of oxygen-poor ocean regions.[18] For Indigenous communities, the degradation of oxygen-depleted marine zones is not an abstract scientific concept but a lived reality, an echo of their ancestors’ suffering. This spiritual and ancestral vision of the ocean places them on the front lines of protecting this vital environment. In contrast, for many Westerners, these issues often remain abstract concepts, discussed in diplomatic speeches but distant from daily life.

On Sunday, June 8, World Oceans Day, La Baleine remained closed to the public. The events prepared the day before then took shape. The screening of the film Remathau: People of the Ocean marked the official opening of UNOC in Nice, as part of a panel titled Women of the Ocean, bringing together iconic figures such as Sylvia Earle, Dawn Wright, Lysa Wini, Aulani Wilhelm, and Nicole Yamase. Remathau tells the story of a young marine biologist from Micronesia who explores the ocean’s depths and simultaneously rediscovers her roots and the strength of her people. The film also aims to raise awareness of Micronesians’ unique relationship with the sea and honour knowledge passed down through generations via legends, songs, and rituals. This powerful moment was accompanied by a performance by John Taukave M.A and Mia Kami with a poignant message, a true declaration of intent for the days ahead:

“There is strength, there is power, and there is change in you and I.

Like the wind, we still move.

Like the waves, we rise high.

Like the sun, we never die.”

Like the marine mammals—kin of Indigenous families, bound by relational ties—the work of women too often fades into invisibility, just as voices go unheard in the silence. In that quiet, feigned ignorance becomes a subtle excuse, allowing violence to linger unchallenged. Yet within this somber truth lies a flicker of hope: that science, when it truly opens—with heart, ethics, and shared purpose—can shift our gaze. And in its embrace, recognise in every being, human or not, a soul both sensitive and complex, utterly unique and irreplaceable.

Acknowledgments. I warmly thank the Odipers group for the richness of the exchanges, as well as for the early morning and late evening meetings in Nice. I also wish to express my gratitude to Alix Levain, Gaëlle Ronsin, and Joanne Clavel for their valuable feedback before the publication of this paper.

– – –

[1] Elsler, Laura G. et al. 2025 [in press] “Leave no one behind in the UN Ocean Decade”, One Earth. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2025.101344.

[2] Johannesen, Ellen, Barz, Fanny, Dankel, Dorothy J., & Sarah B. M. Kraak. 2023. “Gender and early career status: variables of participation at an international marine science conference,” ICES Journal of Marine Science, Volume 80, Issue 4, Pages 1016–1027, https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsad028.

[3] Hills, Jeremy, Chand, Kevin, George, Mimi, Huffer, Elise, Kruger, Jens, Samuwai, Jale, Soapi, Katy, and Anita Smith. 2022. “Blue Heritage in the Blue Pacific.” In Boswell, Rosabelle, O’Kane, David and Jeremy Hills (eds.) The Palgrave Handbook of Blue Heritage: 273-302. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

[4] Nelson, Kate “Inside the Fight for Indigenous Data Sovereignty.” Published on 2.06.2024. Atmos. Earth online.

[5] Vierros, Marjo K., Harrison, Autumn-Lynn, Sloat, Matthew, Crespo, Guillermo O., Moore, Jonathan W., Dunn, Daniel C., Ota, Yoshitaka, Cisneros-Montemayor, Andrés M., Shillinger, George L., Watson, Trisha K., & Hugh Govan. 2020. “Considering indigenous peoples and local communities in governance of the global ocean commons.” Marine Policy 119, September:1-13.

[6] Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. 2016 [2014]. Epistemologies of the South: Justice against Epistemicide. London; New York: Routledge.

[7] Todd, Zoe. 2015. “Indigenizing the Anthropocene” in Heather Davis and Etienne Turpin (eds.) Art in the Anthropocene: Encounters Among Aesthetics, Politics, Environment and Epistemology: 241-254. London: Open Humanities Press.

[8] Krenak, Ailton. 2024. Ancestral Future. Polity.

[9] Leblic, Isabelle. 1989. “Notes sur les fonctions symboliques et rituelles de quelques animaux marins pour certains clans de Nouvelle-Calédonie.” Anthropozoologica NS(3): 187–196. | Luomala, Katherine. 1984. Shark and shark fishing in the culture of Gilbert Islands. Akademia Kiado. | Oliver, D. 1974. Ancient Tahitian society. University of Hawai’i Press.

[10] Ibid., note 5.

[11] Chauvin, Hortense « Les poissons, des êtres sensibles et conscients, loin de nos regards. » Publié le 7 mai 2025. Reporterre, en ligne.

[12] Ibid., note 11.

[13] https://www.oceanopolis.com/le-narval-cet-animal-qui-murmure-a-loreille-des-hommes/

[14] In Reo Tahiti, Papa refers to the original land, the foundation, sometimes linked to the goddess Papa (or Papahānaumoku in Hawaiian), a maternal figure in several Polynesian cosmogonies. It can also mean a layer, the base, or the substrate in a geological or symbolic sense (seabed, reef, genealogical foundation). Chave-Dartoen, Sophie and Bruno Saura. 2018. “Les généalogies polynésiennes, une mise en récit du monde sociocosmique, de son origine et de son ordre,” Cahiers de littérature orale, 84 [Online, accessed June 14, 2025].

[15] David, Victor. 2021. “The Recognition of the Pacific Ocean as a Legal Subject. Contribution to a Biodiversity Without Borders.” In Yenny Vega Cárdenas & Daniel Turp (eds.), A Legal Personality for the Saint Lawrence River and Rivers of the World. ISBN 9782897991579. hal-04935706. | Keynote 1 at the OOSC: “Ocean Rights: Human and Non-Human Rights to a Healthy Ocean,” presented by Michelle Bender.

[16] Gattuso, Jean-Pierre, Duarte, Carlos M., Fortunat, Joos & Laurent Bopp. “Humans will always have oxygen to breathe, but we can’t say the same for ocean life.” Published on 12.08.2021. The Conversation online.

[17] Breitburg, Denise et al. 2018. “Declining oxygen in the global ocean and coastal waters.” SCIENCE vol. 359 vol. 6371. DOI: 10.1126/science.aam7240.

[18] Ibid., note 16.

Share